Web Font Anti-Patterns: Inlining

October 13, 2015

A very common anti-pattern is inlining font files in a stylesheet using base64 encoding. Inlining fonts avoids the overhead of an HTTP request, but that advantage may not outweigh the many downsides.

Inlining is beneficial when you load multiple fonts. Normally a browser needs to create a new connection for each resource. It takes a certain amount of time to create a connection and this cost adds up. When all fonts are combined in the same stylesheet you only need to pay for the connection overhead once. This may seem very attractive, but there are some serious disadvantages to inlining.

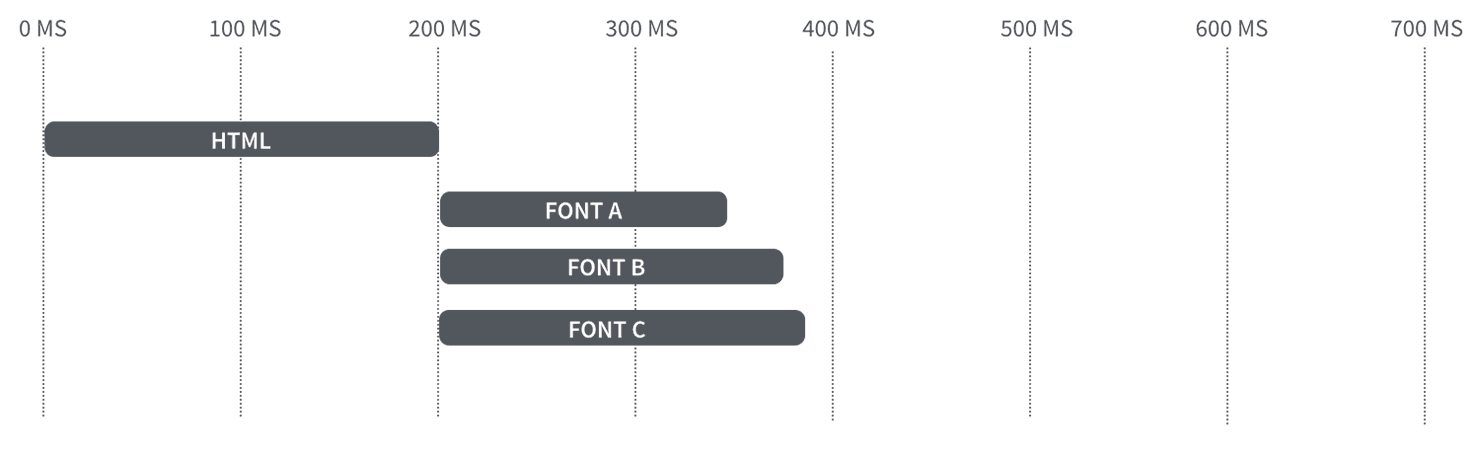

These disadvantages become visible when you compare a network timeline of normal font loading with a network timeline of inlined fonts. Below is a network timeline of the default font loading behaviour. The fonts are downloaded in parallel and render as soon as they finish; font a is rendered first, followed by font b, and finally font c. This is progressive rendering. Fonts are rendered as soon as they finish downloading.

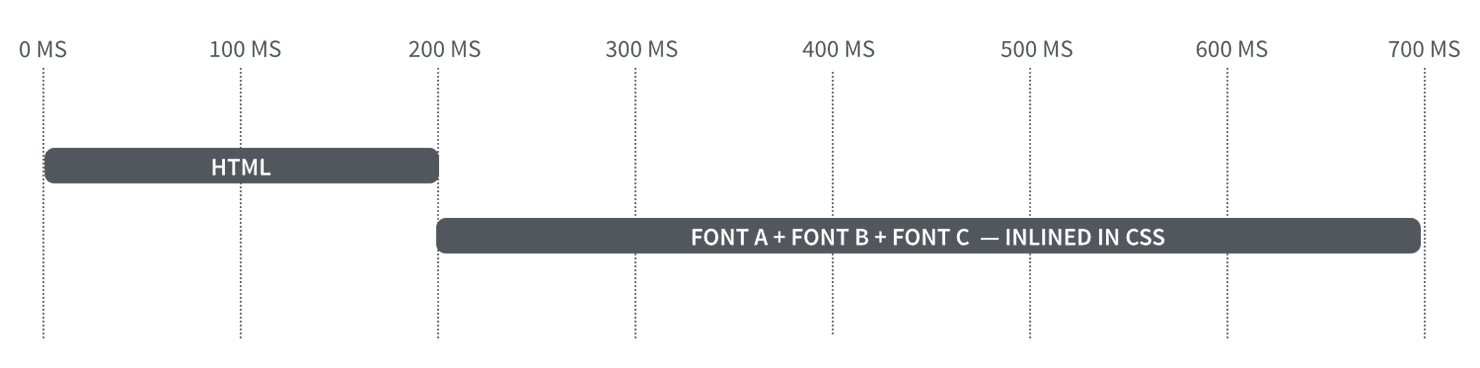

Here is what the timeline looks like when you inline those three fonts in the same stylesheet. Instead of downloading the files in parallel the browser only downloads a single CSS file. This single file is much larger because it contains all three fonts, and takes longer to load than three separate font files downloaded in parallel.

This by itself is already inefficient because browsers can download more than one resource at a time (in fact, many browsers allow up to six connections per host). If you inline fonts you’ll miss out on the benefits of parallel downloads, progressive rendering, and lazy loading.

When you combine all the fonts on your page in a single stylesheet they will all load at the same time: when the stylesheet finishes loading. The browser will normally lazy load fonts by only downloading them if they are used. By inlining all fonts in a stylesheet all of them will be downloaded, even if some are not used on the page.

All of these issues affect web font performance negatively. Remember that fonts should be downloaded with the highest priority and as soon as possible because they block rendering. Inlining will severely impact the actual and perceived performance of your site.

Base64 encoding and decoding

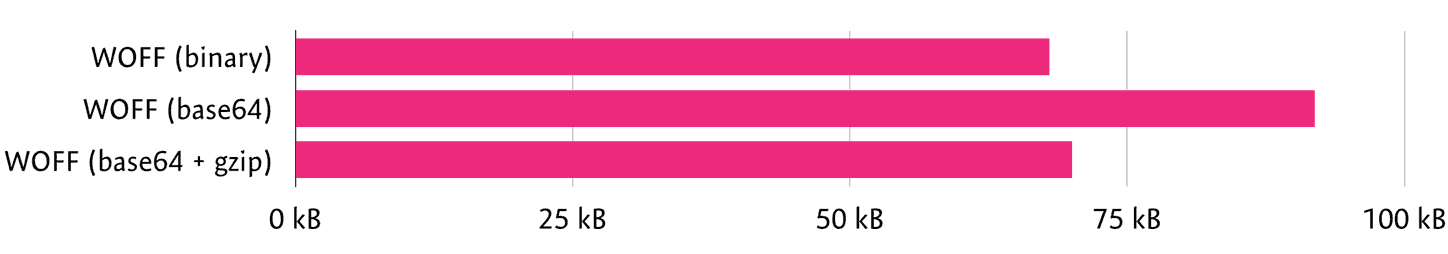

The base64 encoding and decoding also comes at a cost. A base64 encoded file is roughly 30% larger than its binary form. You could negate most of this by using GZIP compression, but the resulting file size will still be slightly larger. Base64 decoding doesn’t come for free either. Fonts embedded in a stylesheet using base64 encoding will need to be decoded before they can be parsed. This cost is insignificant on most desktop computers, but can be problematic on devices with less powerful processors such as tablets and mobile phones.

Average WOFF file size out of a 20.000 font file corpus. Base64 encoding the WOFF file increases the file size by about 30%, but GZIP compression reduces this to close to the original file size.

Font format negotiation

Another big problem with inlining is that it limits you to a single web font format. Because the entire font file is inlined in CSS, adding support for another font format increases the size of the CSS file (essentially you would be storing and transmitting the same font once per format). You could work around this by trying to guess the web font format support based on the browser’s user agent string, but this is a rabbit hole you don’t want to go down into. (Believe me. I’ve been there — it’s not a happy place.)

If you don’t want to do user agent sniffing you’re left with serving the font format with the widest browser support: WOFF. That’s perhaps sufficient for most websites, but you’ll miss out on the benefits of newer formats that offer much better compression rates, such as WOFF2.

Caching

Finally, inlining also negatively affects caching. If you update one (or multiple) fonts in your stylesheet you’ll need to invalidate the browser cache for the entire stylesheet (for example, by changing the name of the stylesheet). Your visitors will need to re-download the CSS file containing all the fonts even though most of them did not change. If the font files were served (and cached) as individual files only the updated font file would need to be downloaded again, and the remaining files can stay cached.

Closing thoughts

So, to sum up: unless you’re loading a lot of fonts (let’s say more than 10) inlining is a bad idea. It’ll affect your actual and perceived performance, thereby making your site load slower. It also disables font format negotiation, progressive rendering, parallel downloading, and lazy loading.

With the introduction of HTTP/2, inlining is an even less attractive option. HTTP/2 enables parallel downloads over the same connection. This has the same benefit as inlining (avoiding connection overhead) but none of the downsides. Caching, font format negotiation, lazy loading, and progressive rendering will continue to work as expected with HTTP/2. Many browsers, servers, and hosting providers already support HTTP/2, so you can start using it today instead of inlining!

This article is part one of an ongoing series on web font anti-patterns. Read the introduction, part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4.