Detecting System Fonts Without Flash

July 30, 2015

Update 2017-11-04: The latest version of Font Face Observer no longer supports detecting local fonts, so you’ll need to grab an old copy to use the code in this article.

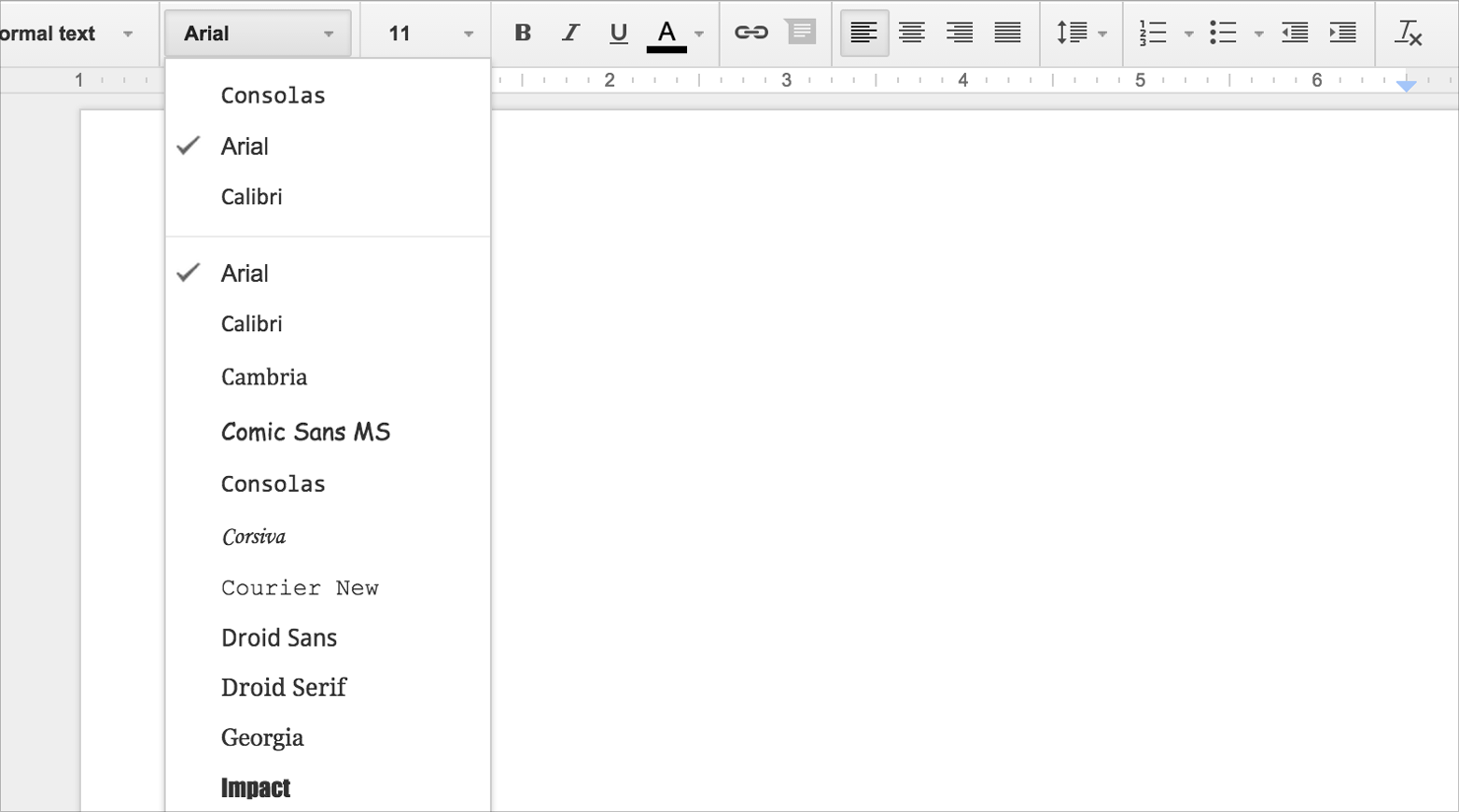

Many web-based text editors allow the user to select custom fonts through a drop down menu. These font menus often include system fonts. Unfortunately, there is no web platform API for retrieving a list of locally installed fonts, so many of these applications rely on a Flash library to detect which fonts are installed on the user’s system.

Besides the recent security issues, there are several good reasons for not using Flash. Its market share has dropped significantly in the last couple of years. There is also a good chance that someone visiting your site will not have Flash installed (pretty much a guarantee on iOS).

So, what should you do when you want to find out which fonts are installed locally? Well, you can actually use plain JavaScript to detect if a font is available or not. Here are some of the system fonts your computer claims to support:

The result of detecting the availability of several common system fonts on your computer. The ones marked with ✓ are available on your computer; the ones marked with ✗ are not.

The example above uses FontFaceObserver, a small JavaScript library I wrote for detecting when a web font loads. Even though FontFaceObserver was created for web fonts, it can also be used to detect locally installed fonts.

To check if a font is available you pass its name to the FontFaceObserver constructor and call the check method. If the returned promise is resolved the font is available locally; if the promise is rejected the font is not available.

var observer = new FontFaceObserver(‘Georgia’);

observer.check().then(function () {

// Georgia is available

}, function () {

// Georgia is not available

});

By doing this for each font in your font menu you can warn the user if some of their choices are not available (or look different).

How does it work?

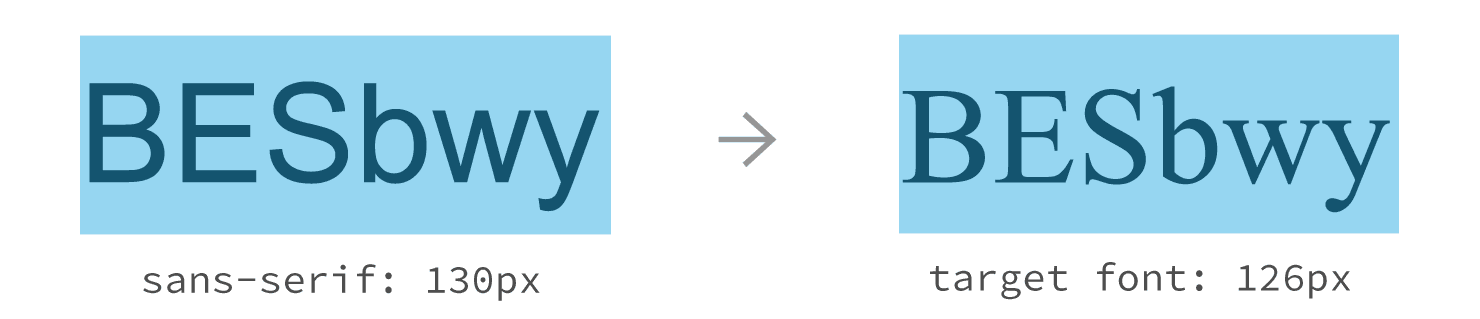

The idea behind FontFaceObserver is very simple: create a span element with a known font family, measure its width, set the target font family, and measure the width again. If there is a difference in the width, you’ll know that the font has rendered and is thus available.

In the example above we use a span element with the string BESbwy rendered in the generic sans-serif font family. The string BESbwy is used because it contains characters that often have different width in many fonts. The initial width of the span using the sans-serif font family is 130 pixels.

We then change the font-family property of the span to include our target font. The target font is found and the browser redraws the span. Because the target font’s metrics (the widths of each individual character) are different the span changes its width to 126 pixels. The difference between the initial width and the target width means that the font is available.

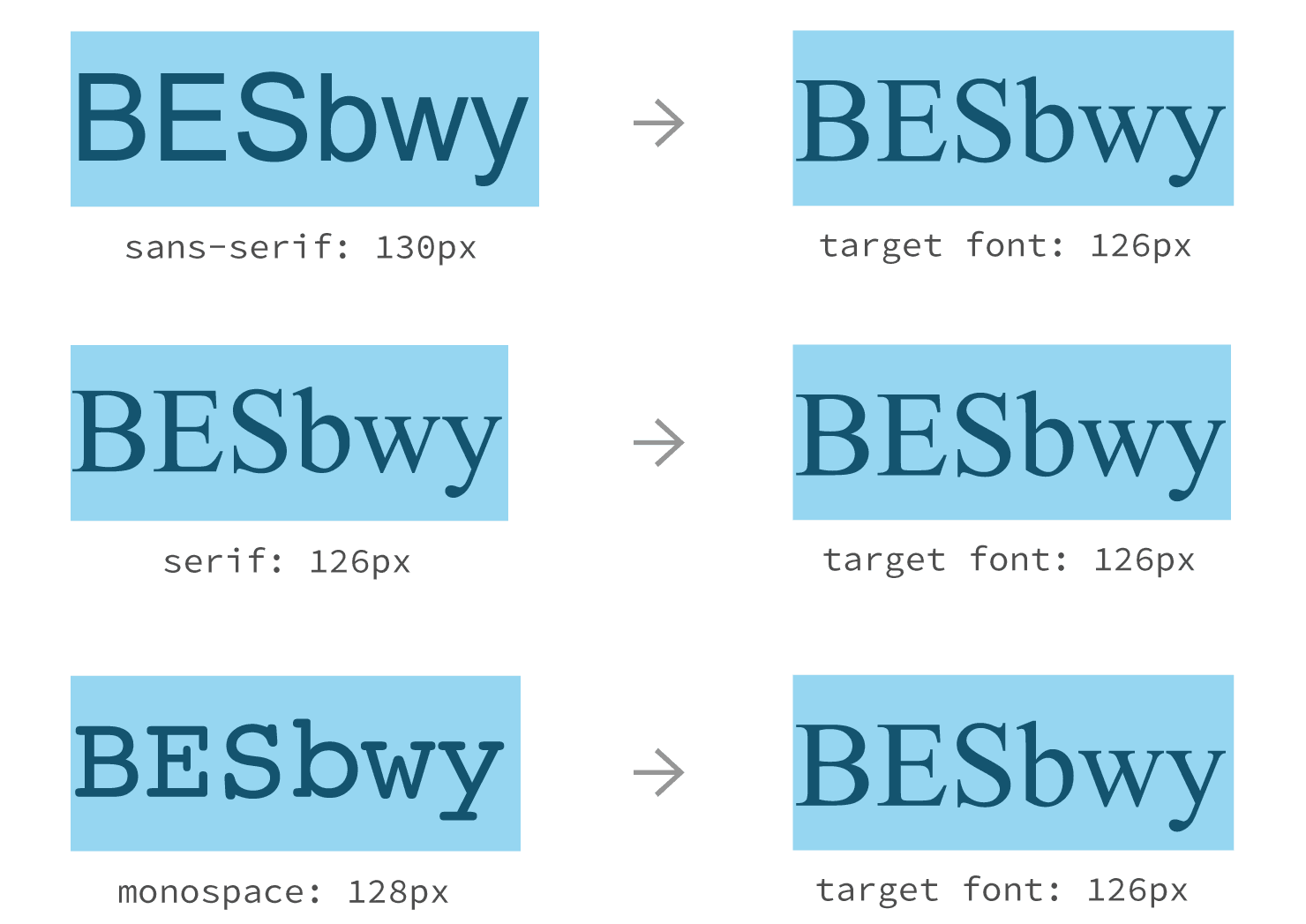

This approach has a problem though. What would happen if the font we’re trying to detect is the same as the generic sans-serif font family? In this case the span would stay the same width and we wouldn’t be able to detect the font. To work around this problem FontFaceObserver uses three spans, one for each of the three generic font families: sans-serif, serif, and monospace.

In this example the font we’re trying to detect is the same as the generic serif font family. If we had used a single span with we wouldn’t be able to detect this font because the initial and target width are the same for the serif span. Because the other two spans have different initial widths we can safely assume the font has rendered and is available for use.

Can I use it?

So how accurate is it? It works well on platforms that are truthful about which fonts are installed. Unfortunately, some platforms lie. For example, Android only ships with three fonts: Droid Sans, Droid Serif, and Droid Sans Monospace (or in more recent versions of Android: Roboto and Noto). Its graphics subsystem maps common font family names to locally installed fonts. This means that from the point of view of the browser those fonts actually exist, even though they are in fact aliases to the same fonts. While this is disappointing, you could argue that those aliases were chosen because they are acceptable substitutes (well, let’s hope so).

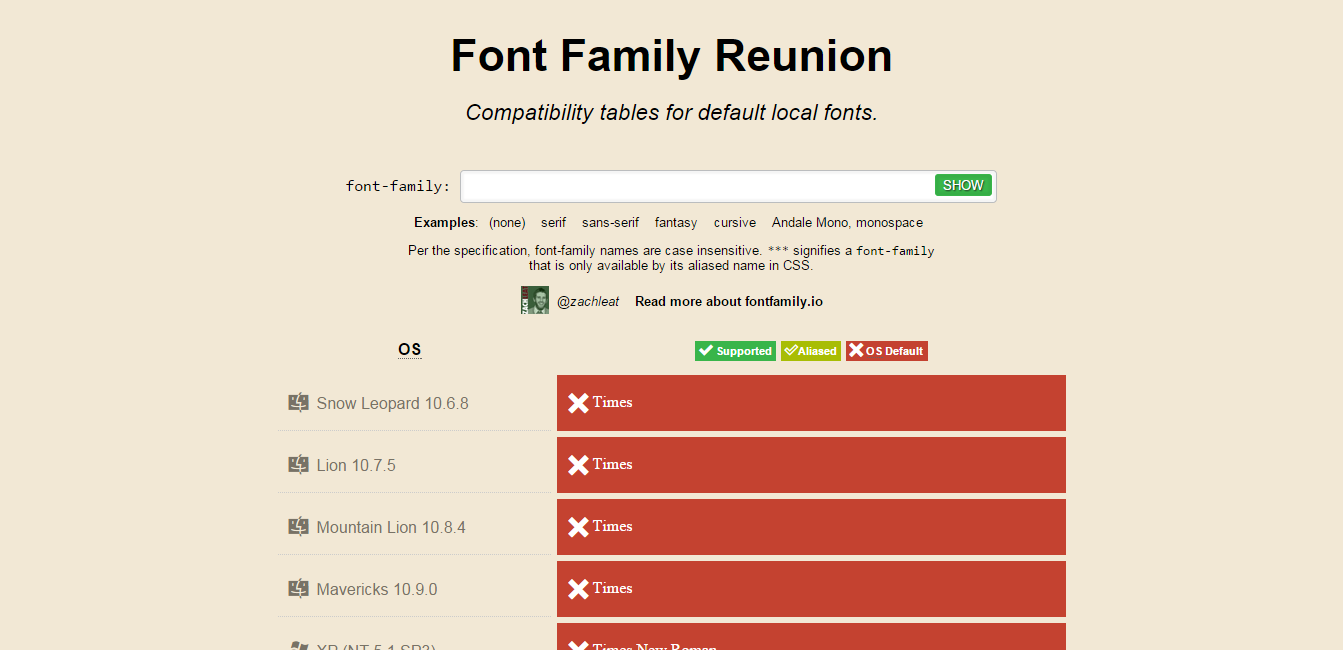

Font aliases are less common on other platforms, but still exist. Zach Leatherman’s fontfamily.io is a great tool to find out which fonts are available on which platforms. It’ll also tell you if a font is aliased or not.

So, is this a reliable way to detect locally installed fonts? It really depends on your goals. I wouldn’t recommend using this to disable items in a font menu. However, it can be a helpful tool to pop up a warning when a “web safe” font isn’t installed locally. In the end, if your web application relies on the presence of a font, it is best to use web fonts instead of local fonts. You can be certain that web fonts will be available no matter the platform.

Credits

Remy Sharp advocates a similar technique in his blog post on “How to detect if a font is installed”. His method relies on Comic Sans as a way to detect the existence of a locally installed font. Unfortunately this is unreliable on platforms that do not have Comic Sans (of which there are many).

Lalit Patel has implemented a similar solution which uses the generic monospace font family. While this is better than using Comic Sans it can report false negatives for system fonts and metric compatible fonts.

Finally, Zach Leatherman uses the same technique for detecting locally installed fonts for fontfamily.io.